Apple’s censorship in Hong Kong

AppleCensorship’s Survey

Apple is China’s Democracy “Kill Switch” in Hong Kong

In the spring of 2021, AppleCensorship conducted a survey of more than 2,500 Hong Kong residents in order to better understand their perception of digital censorship and surveillance since the passing of the national security law, as well as their use of mobile apps and how they communicate and access information.

• Hong Kongers rely on mobile apps that are banned in China to communicate and access information:

We found out that 27% of Hong Kong residents were using WhatsApp, while 24% rely on WeChat. Facebook’s Messenger, Signal and Telegram are each used by less than 10% of the respondents (Messenger 0%, Signal 7%, Telegram 6%). 11% of the respondents are using different apps or communication tools to send their messages (e.g. Viber, Line, Threema, Skype, etc.).

Respondents also use social networks (apps and/or their web version) as their main source of general information and daily news. While Hong Kong based websites remain the most used source of information (13%), Facebook is the primary source of information for 10% of the population, while WhatsApp, Telegram and Twitter each constitute the main source of news for 5% of Hong Kongers. Although less used than WeChat (8%) Weibo (5%), Instagram is used by 4% of the population as its main source of news. Chinese language media, Foreign news (sites and/or apps) and online forums are also favored by 5% and 7% respectively. 28% of the population is using other unspecified sources.

Those figures make it clear that Hong Kong residents massively rely on online services and apps that are blocked in mainland China and could disappear from Hong Kong as pressure from the authorities arises.

• Hong Kongers are worried about the impact of the NSL on their digital freedoms.

More than 70% of the residents would feel concerned if mobile app stores started censoring apps at the behest of the authorities, and 25% believe that online censorship (the blocking of websites and social networks) will occur within the next five years. Although the level of restrictions is not yet comparable to that of mainland China, 28% of the population thinks that such online censorship is already present in Hong Kong. 43% believes that between one and one hundred websites have been blocked since the passing of the NSL. Hong Kongers are also worried about surveillance. 52% of the people have become more careful about what information they post online, and 44% believe that the authorities are tracking their online activity.

Yet, only 37% of the Hong Kongers have installed or subscribed to a VPN app or other similar service on their mobile device or personal computer.

Apple’s Presence in Hong Kong: A Threat to Freedom of Information

The results of the survey confirm that Hong Kongers rely significantly on social media apps and services to communicate with each other and to seek news and information. They also highlight the growing concern that the national security law may impact their digital freedom and lead to an increase of online censorship and surveillance. A market research conducted by Digital Business Lab and Standard Insights at the beginning of the year confirms both Hong Kongers’ reliance on social networks (such as WhatsApp and Instagram), and increased concern regarding the national security law. In their survey, “the majority of respondents (68% of a panel composed by individuals belonging to the “Gen Z” and “millennial” categories) expressed concern about possible limits on social media and communications in Hong Kong. Only 8% of the respondents said they were using a VPN, a result significantly lower than the 37% obtained by AppleCensorship’s survey.

Other results reveal that respondents would be open to Chinese “replacement platforms” should their preferred one become unavailable: WeChat, Douyin and Xiaohongshu (RED) could become their app of choice as a replacement for Instagram, Youtube, Whatsapp, LinkedIn or Facebook. It is worth noting that for three out of these five apps, the first answer given by the respondents is “none of the above”, meaning that they would not replace the app should it become unavailable.

As various market intelligence firms estimate Apple’s market share in Hong Kong is between 45% and 53%, the picture that starts to appear when trying to anticipate further restrictions on freedom of information and expression in Hong Kong, is a very dark one.

Should Beijing decide to crackdown on social media and social networking apps in Hong Kong, all it would have to do is ask Apple to remove apps that it deems illegal or that it accuses of violating the NSL, and overnight, almost half of the population of Hong Kong would lose access to dozens of apps, if not more, to many independent sources of information and to platforms where they usually exchange information with their networks. Part of these users would not replace the apps that have become unavailable, while another significant part would simply switch to China’s “replacement apps”, exposing themselves further to censorship and surveillance. Only a fraction of the users would have the ability to use their already acquired VPNs, while the majority of iOS users would be left without any solution, as VPN apps would logically be included on the list of banned apps along with the social media and networking apps targeted by the authorities.

Apps at Risk : The National Security Law, Censorship & Hong Kong’s Steep Road to Authoritarianism

On 30 June 2020, the national security law was passed by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, and came into force the same day. Despite authorities reassurance that the law would target “an extremely small minority of illegal and criminal acts” and that the “basic rights and freedoms of the overwhelming majority of citizens (would) be protected”, the NSL severely impacted press freedom and free expression, offline and online.

Authorities have used the NSL to harass members of civil society organizations, human rights workers, activists and journalists. And to justify censorship of any content deemed to constitute one of the four types of activities criminalized by the NSL: secession or separatism, subversion, terrorism and collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security.

Over the last two years, the space for media and internet freedom in Hong Kong has shrunk considerably, transforming Hong Kong into an authoritarian territory where censorship, and now self-censorship, are gradually becoming the rule rather than the exception. In July 2021, a story that portrayed the police as wolves preying on sheep (activists), led to the arrests of five people behind the book’s publication.

Under the NSL, internet service providers, telecommunication operators, those who manage social networks and online platforms and those operating the numerous data centers in Hong Kong face greater liability for user content. In such a repressive environment, Apple’s App Store may become one of the key targets for the authorities when they will be looking to restrict access to certain contents online.

Looking at the impact of the NSL on freedom of information and expression in Hong Kong over the last two years, AppleCensorship provides a non-exhaustive list of media and social media apps that have been directly or indirectly impacted by the NSL or that could be at risk of being targeted by the authorities in the future.

1. Social Media

Facebook

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Available

Status in China’s App Store: Available but blocked

Risk of removal: Medium

In May 2020, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg expressed concern about the situation in Hong Kong and Facebook’s ability to operate on the territory and continue to offer its services such as WhatsApp, which allows users to communicate safely via end-to-end encrypted messages.

At the end of 2020, some pro-democracy groups on Facebook were suspended, such as the page called Tai Po, which had 120,000 members when it was suspended and frequently hosted messages supportive of the protests. Facebook has removed several popular pages run by pro-democracy and pro-police groups without explanation. While pressure on Facebook is expected to grow, the company has a better chance at resisting censorship than smaller social media platforms, and Apple knows that the removal of the platform from its APp Store would not go unnoticed.

MeWe Network

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Available

Status in China’s App Store: Unavailable

Risk of removal: High

After Facebook suspended pro-democracy groups and pages supporting the protests, fears that Facebook could be cracking down on anti-China messages led many of its users to switch to other platforms with fewer rules for content moderation. MeWe has been one of the main alternatives cited by Hong Kongers. Some independent media, such as Inmediahk.net, host some of their content on the platform.

LIHKG (討論區)

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Available

Status in China’s App Store: Unavailable

Risk of removal: High

Established in 2016, LIHKG is a forum which gained popularity and gradually replaced a formerly prominent Hong Kong forum called HKGolden as the go-to site for Hong Kongers to discuss political content. LIHKG is often compared to Reddit (available in Hong Kong but unavailable in China’s App Store), where users create threads and submit a variety of content through relevant “subreddits” that categorize the posts into different sections.

Similar apps at risk:

Telegram Messenger

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Available

Status in China’s App Store: Available but blocked

Risk of removal: Medium

The number of arrests and prosecutions for content posted online has increased since the adoption of the NSL.

In June 2019, Ivan Ip, 22, who allegedly administered a group channel on Telegram called “Parade 69”, named for a mass demonstration planned in central Hong Kong to protest the “extradition bill”, was arrested on “suspicion of conspiracy to cause a public nuisance”. In April 2021, a Hong Kong court sentenced 26-year-old Hui Pui-yee, who helped run a Telegram channel during the 2019 protests, to three years in jail, for “conspiracy to commit a seditious act and conspiracy to incite others to commit arson”. In May 2022, 27-year-old Ng Man-ho, who had run a Telegram Channel with more than 109,000 subscribers during the 2019 and 2020 protests, was jailed for six and a half years after being convicted of “conspiring to incite others to commit arson”, “rioting” and other crimes.

Some local media outlets reported that the Hong Kong government is considering restricting access to Telegram.

Rumble

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Unavailable

Status in China’s App Store: Unavailable

Risk of removal: Low to Medium

Presenting itself as a Youtube alternative, Rumble is trending online video platform and cloud services business, which, despite being its limited accessibility (the app is currently only available in 10 App Stores), has already convinced several major media companies like the Reuters and the NY Post, to run their own channel on the platform. In 2021, Stand News (see here) created its own channel, although it uploaded very few videos (or they have since been removed). The fact that the apps is already unavailable makes it an improbable target for the authorities. But if the number of Hong Kongers equipped with VPNs using the platform continues to grow, the app could attract Beijing’s attention.

2. Media

The NSL has taken a serious toll on press freedom and freedom of information. Journalists have been arrested for merely doing their job, criminal charges have been brought against critical journalists and media outlets, even retroactively.

When it comes to “traditional media”, the authorities often favor strategies that instill self-censorship within the media personnel before resorting to outright censorship. This makes the probability of news and media app removal slightly lower than that of social networking and other apps used by the civil society.

In Hong Kong, authorities now regularly threaten media and media personnel with prosecution under the NSL and sedition law for their coverage of the government or for spreading “fake news”. On 7th October 2022, a Hong Kong court sentenced radio host and political commentator Edmund Wan Yiu-sing to two years and eight months in prison under the rarely-used colonial-era sedition law.

D100 Radio HK

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Unavailable

Status in China’s App Store: Unavailable (previously available)

Risk of removal: Medium

Hong Kong D100 internet radio channel host Edmund Wan Yiu-sing, better known as “Giggs”, 54, was sentenced on 7th October 2022 to a total of two years and eight months in prison for “sedition” under a rarely-used colonial-era law, and for alleged “money laundering”. He was also ordered to hand over HK$ 4.87 million (about € 633,000) of his assets.

Hong Kong internet radio host Edmund Wan Yiu-sing sentenced to 32 months in prison

Apple Daily (蘋果動新聞)

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Available

Status in China’s App Store: Unavailable

Risk of removal: Medium

The crackdown and closure of Apple Daily is emblematic of how the NSL is being used to stifle press freedom. It is reflective of the CCP’s tactic to target key individuals in order to send a warning signal to others of the risks of speaking out and challenging the party’s authoritarian rule. The crackdown on Apple Daily also reinforced the retroactive nature of the NSL.

Apple Daily released its final edition on June 24, 2021 and shut down its website, online television channels, and social media accounts following an unprecedented police raid and the arrests of its chief editor, other newsroom staff, and executives at the parent company Next Digital, all under the NSL.

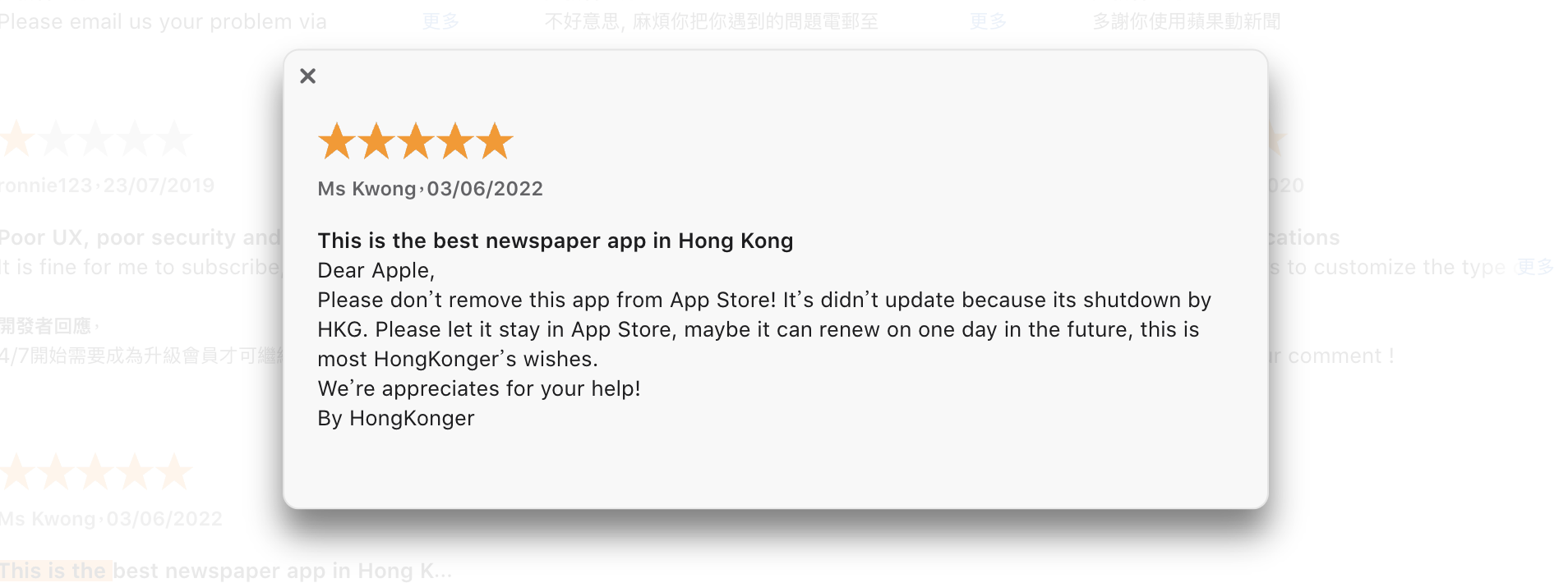

However, until today, Apple Daily’s app is still available in the App Store, and is only blocked in China’s App Store. Some users have even requested Apple to keep the app in the App Store until the media is reformed, while several initiatives to archive the journal’s content (and other media at risk) have emerged.

The website collection.news, which archives content from both Apple Daily and Stand News, has saved more than 400,000 articles from Apple Daily.

Similar apps at risk:

Hong Kong Free Press

Apple Daily Taiwan

Next Magazine (壹週刊)

Next Apple News

Apple Daily’s sister publication, Next Magazine, was also shutdown in 2021, with the app still available in the App Store.

Apple Daily Taiwan, Taiwan’s version of the Hong Kong pro-democracy tabloid, quickly became one of the major media outlets in Taiwan after having entered the market in the 2000s. As the crackdown on Apple Daily in Hong Kong started, the fate of Apple Daily Taiwan was uncertain until it eventually discontinued its print edition in May 2021, to focus on its online version. The media eventually shut down and was rebranded as “Next Apple News” in August 2022, under the ownership of Singaporean entrepreneur Joseph Phua. In a statement published on the 30th Apple Daily Taiwan staff, which almost entirely moved to Next Apple News, said it was “sorry that it had to bid farewell to its readers due to a lack of working capital, but added that Next Apple News would continue to shoulder the same responsibility to expose societal injustices.

RTHK

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Available

Status in China’s App Store: Available

Risk of removal: Low to Medium

The overhaul of public broadcaster RTHK by the government has been one of the most severe blow to press freedom in Hong Kong since the adoption of the NSL. Once a respected source of information, RTHK started to lose its editorial independence in February 2021 after a government review found “deficiencies in the editorial management mechanism and a lack of transparency in handling complaints”. RTHK also suspended its relay of the BBC radio news after China’s ban of the BBC World News broadcasts. From March until August 2021, RTHK cancelled a current affairs program, removed content from its online archives and its Twitter account, launched a chat show hosted Hong Kong Chief Executive, issued directives to its journalists to use Beijing-approved wording in their reporting activities, and started a partnership. RTHK has also seen an exodus of senior editorial staffers. Employees were also warned that they would be held financially liable for airing forbidden content.

In May, RTHK confirmed that it had begun removing shows older than 12 months from its YouTube channel and Facebook page. A couple of months later, RTHK’s English-language Twitter account was also purged from its earlier posts. Considering the extent of the media’s overhaul, the probability of the Beijing requesting that the app be taken down is low.

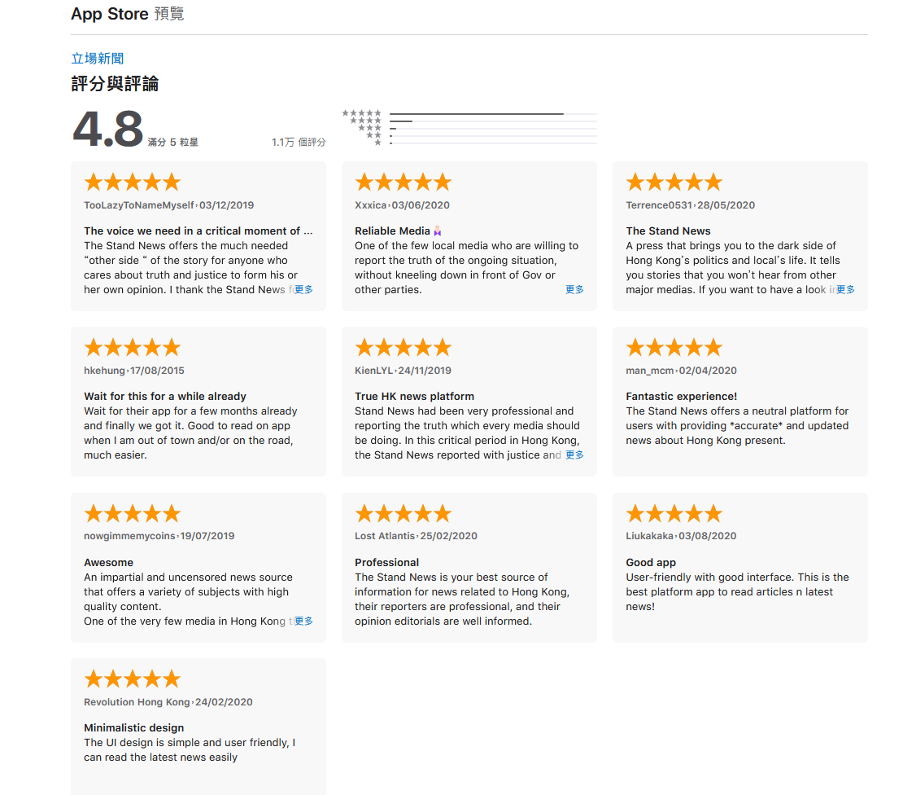

Stand News (立場新聞)

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Disappeared (app removed globally)

Status in China’s App Store: Disappeared (app removed globally)

Risk of removal: N/A

After the shut-down of Apple Daily, Stand News was one of the few remaining pro-democracy media outlets in Hong Kong. But on 29 December 2021 at 6.20 am, over 200 police officers raided Stand News’ office, seizing boxes of evidence and arresting several current and former senior staff. They also searched the residence of Ronson Chan, who was at the time Stand News’ deputy assignment editor and chair of the Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA). Stand News’ assets (HK$61 million) were frozen and, on the same day, the company announced that it was ceasing its operations.

Stand News’ iOS app remained available for download in the App Store until at least December 2021, but was eventually taken down globally around the same time the news outlet’s UK office chief, Yeung Tin-shui announced the decision to cease operations of Stand News’ UK office. All reporting on the Stand News website provided by the UK office and its social media accounts were also removed. It is unclear if the removal was initiated by Stand News staff or ordered by the authorities.

Comments posted during the time of the protests praising Stand News can be seen on the app’s page in the App Store (archive)

Initium (端傳媒:華語深度新聞)

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Available

Status in China’s App Store: Unavailable

Risk of removal: Medium to High

A digital news outlet launched in 2015 in Hong Kong, and specializing in in-depth feature reporting on issues in Hong Kong, Taiwan and mainland China, Initium announced in August 2022 that it was relocating its headquarters to Singapore, to “produce content through online and decentralized medium, and continue to present the pulse of the times in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan in our in-depth content”, said Initium’s executive editor. This move made Initium the first Hong Kong-registered media to relocate abroad as a result of the national security law. Although the media relocated abroad, its local reporters remain a target of choice for the authorities, should they attempt to silence the media or force it into self-censorship, making an app takedown request less likely.

South China Morning Post (SCMP)

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Available

Status in China’s App Store: Available

Risk of removal: Low

In March 2022, Gary Liu, Alibaba-owned South China Morning Post’s CEO, quit his role after six years at the helm of Hong Kong’s oldest English-language newspaper, bringing more uncertainty on the future ownership of the media. Speaking about editorial line of the SCMP company, journalist and former SCMP contributor Stephen Vines wrote in 2018:

“Most of the critical voices have been purged from its comment pages leaving a stodgy residue of required reading for insomniacs. Sprinkled on top are some “brave” critics whose licence to criticise is conditional on their readiness to disparage Hong Kong’s home-grown democratic forces.

There are a couple of significant exceptions, but they would understandably not wish to be named as it would jeopardise their positions.”

i-CABLE (流動版)

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Available

Status in China’s App Store: Available

Risk of removal: Low

Hong Kong television station i-Cable TV network was founded in 1993 and is now owned by David Chiu, chairman and CEO of Far East Consortium. In December 2020, Executives at Hong Kong television station i-Cable TV network announced they would be firing at least 40 journalists, editors, and production crew, including the team of the award-winning investigative journalism show News Lancet. “The Group needed to conduct a comprehensive review and adjustment of personnel and leadership structure across all departments.”, an official statement said.

Epoch Times (大纪元)

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Available

Status in China’s App Store: Unavailable

Risk of removal: Medium

While physical attacks on individual journalists remain rare, their number has increased over the years. The attack on the printing press of the Epoch Times newspaper is one of the most recent examples of the growing threat on news providers. The newspaper, which was founded by practitioners of the Falun Gong spiritual movement, often covers human rights abuses in mainland China and is fiercely critical of the CCP. Between April and May 2021, unidentified attackers assaulted an Epoch Times journalist with a baseball bat and broke into the journal’s printing facility and damaged the office’s computers and printing machines.

Related apps:

MINGHUI (news of the Falun Gong community)

The Witness (法庭線)

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: no iOS app

Status in China’s App Store: no iOS app

Risk of removal: Medium to High

While prominent independent outlets, such as Apple Daily and Stand News, have shut down one after another, a number of independent media outlets are still trying to report on Hong Kong current affairs independently. The Witness, which started publishing in May 2022 was launched by a “group of former court reporters” aiming at restoring a proper coverage of legal affairs (i.e. including cases related to the national security law).

Although the media does not have any mobile app, it is widely present on social media platforms. The Witness has a Facebook page, an Instagram and a twitter account, a Telegram Channel, and a Youtube video channel with already more than 5,000 subscribers.

It is yet to be seen if such model of online presence, chosen by several independent media which have recently formed in Hong Kong, constitutes a strength and higher capacity of resilience to censorship or, in the contrary, if it makes the media vulnerable to the authorities’ control of the internet. As The Witness also relies on membership platform Patreon, to finance its operations, the removal of the platform from Hong Kong’s App Store (coupled with the blocking of the website) could cut the media from its main source of income.

Apps at risk:

3. Civil Society

Human Rights Academy (Amnesty International)

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Available

Status in China’s App Store: Available

Risk of removal: Low to Medium

In August 2019, human rights organization Amnesty International revealed it had “been the target of a sophisticated state-sponsored cyber-attack, consistent with those carried out by hostile groups linked to the Chinese government. The attack had first been detected on 15 March 2019, when “state-of-the-art security monitoring tools detected suspicious activity on Amnesty International Hong Kong’s local IT systems”. Two years later, in October 2021, the organization announced that it had no other choice but to close its offices in Hong Kong “by the end of the year”.

“This decision, made with a heavy heart, has been driven by Hong Kong’s national security law, which has made it effectively impossible for human rights organizations in Hong Kong to work freely and without fear of serious reprisals from the government,” Anjhula Mya Singh Bais, chair of Amnesty’s International Board was quoted as saying in the statement.

In 2020, the organization launched its Human Rights Academy app, which offers a wide variety of human rights courses in more than 20 languages, including Chinese. As Beijing’s goal was to see the group depart from Hong Kong, it is unlikely it will seek to take down the app.

Similar apps:

Yellow Umbrella (黃雨傘)

Status in Hong Kong’s App Store: Available

Status in China’s App Store: Unavailable

Risk of removal: Low to Medium

The app Yellow Umbrella was created in 2014 to gather the RSS feed of all Twitter news related to the Umbrella Revolution in Hong Kong, including the Occupy Central with Love and Peace civil disobedience campaign, students’ engagement and demonstrations. The app could fall into Beijing’s plans to purge Hong Kong’s App Store of all seditious content.

iCensorship

Apple has bet big on China, a strategy shaped by Tim Cook soon after he joined the company two decades ago and took charge of its operations. The bulk of its factories are there, and as of last year, almost half of its key suppliers for core inputs like chips and glass are based in China. Most of Apple’s supply chain is now in China as well as 1/5 of Apple’s annual revenue ($17.7 billion net sales in Q1 2021). Apple’s suppliers became more concentrated in China. Among all supplier locations, 44.9% were in China in 2015, a proportion that rose to 47.6% by 2019, the data showed.

Apple faces hurdles in diversifying beyond China, where the clustering of multiple suppliers allows it to make hundreds of millions of devices per year while holding only a few days’ worth of inventory, which is critical to the free cash flow Apple investors prize. Other phone makers ship far fewer units and have more flexibility. Even if Apple can make devices in India or Vietnam, the volumes would be small compared with Apple’s overall needs. Outside of China, there are few places in the world that have the infrastructure to produce 600,000 phones a day.

In 2019, Cook took on the role as board chairman of the business school at China’s prestigious Tsinghua University. The university, known as “China’s Harvard,” has a storied history as a cradle of Chinese political and economic thought. Cook accepted the promotion to board chair in 2019 in the midst of Hong Kong protests and Apple’s take-down of HKMaps. In 2019, Cook also met with China’s top market regulator to talk about Apple’s investment and business development in China and Cook told attendees at a conference in Beijing that his company was “grateful” that China had opened its doors to Apple.

“We encourage China to continue to open up,” Cook said at the China Development Forum. “We see that as essential, not only for China to reach its full potential, but for the global economy to thrive. … Our future, therefore, depends on collaboration.”

During the 2019 protests, Apple removed apps that protesters used to organize themselves during the uprising, and Apple did not join the coalition of tech platforms that announced they would not disclose data to the Hong Kong authorities.

In 2020, a Hong Kong resident reported that he requested to have the phrase “liberate HKERS” [Hong Kongers] engraved on an Apple product. He said an Apple employee contacted him over the phone, refusing to communicate in writing, and refused to provide the engraving as requested because the Apple “higher-ups did not approve” of the message.

While Apple promotes itself as a company advocating for human rights and opposing North American law enforcement requests when they are unjust, The Citizen Lab researchers have discovered instances of Apple’s censorship in Hong Kong through “broad, keyword-based political censorship” and displayed through App Store app take-downs, removed media content, and even the product engraving process (see here). Apple has even forbidden their own employees in Hong Kong from wearing any attire that would imply support for Hong Kong independence from China.

The New York Times found that Apple proactively censors its Chinese App Store, relying on software and employees to flag and block apps that Apple managers worry could run afoul of Chinese officials.

The New York Times found that Apple built a system that is designed to proactively take down apps — without direct orders from the Chinese government — that Apple has deemed off limits in China, or that Apple believes will upset Chinese officials. The system includes training app reviewers on a long list of topics that it believes are not permitted in China and creating software that searches for those topics.

In Hong Kong, Apple is known to broadly censor references to collective action including 雨伞革命 (Umbrella Revolution), 香港民运 (Hong Kong Democratic Movement), 雙普選 (double universal suffrage), and 新聞自由 (freedom of the press). Apple also censors references to political dissidents such as 余杰 (Yu Jie), 刘霞 (Liu Xia), 封从德 (Feng Congde), and 艾未未 (Ai Weiwei).

Much of Apple’s censorship in Hong Kong is not required by local Hong Kong laws and regulations. Researchers say Apple may apply its mainland China censorship in Hong Kong intentionally, which “speaks to how much Apple wants to appease the Chinese government.”

“Apple has become a cog in the censorship machine that presents a government-controlled version of the internet. If you look at the behavior of the Chinese government, you don’t see any resistance from Apple — no history of standing up for the principles that Apple claims to be so attached to,” said Nicholas Bequelin, Asia director for the Human RIghts NGO Amnesty International.

Apple Movies & Books

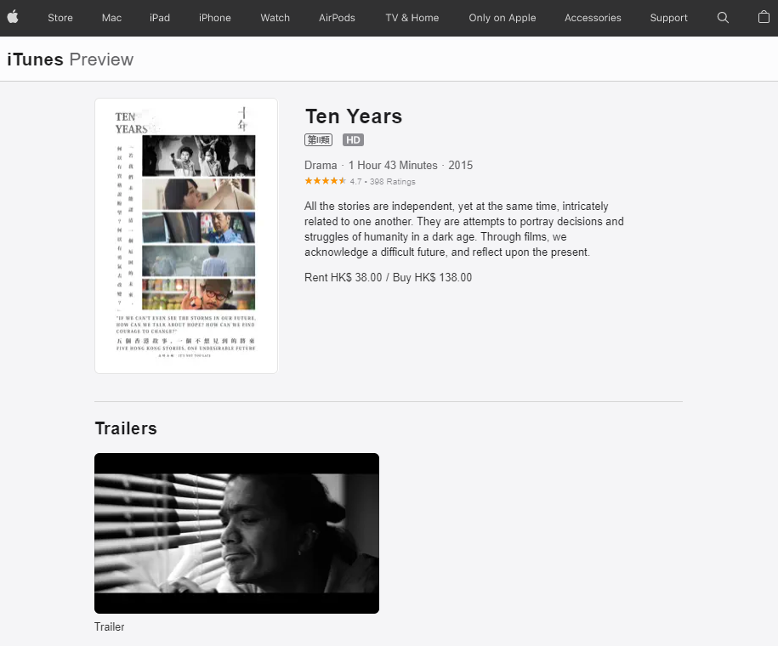

In 2016, Beijing blocked Apple’s iTunes Movies and iBooks Stores in China, only six months after they had launched. The shutdown occurred shortly before the Hong Kong film “Ten Years” (十年), already censored in China, was released in Apple’s Hong Kong iTunes service. The 2015 film imagined Hong Kong overtaken by Beijing in 2025: with paramilitary, protests & “language police.”

The Chinese Communist Party called the film a “thought virus.” Subsequently, the Chinese content regulator, the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT, abolished in 2018), ordered the Apple services shut down. Today, the film’s page on itunes seems to be unavailable globally.

In April 2017, satirical news show China Uncensored, which is affiliated with the religious group Falung Gong, claimed that the Apple TV service blocked users from accessing it from Hong Kong and Taiwan in addition to mainland China. The show which was launched on YouTube in 2012 and aired by New York-based New Tang Dynasty Television (NTD.TV), had been approved by Apple in March 2017 before being removed from Apple TV App Stores in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Apple’s legal team justified its decision, saying the company had to comply with local laws.

In a message sent to China Uncensored, Apple said:

“Apps must comply with all legal requirements in any location where you make them available (if you’re not sure, check with a lawyer). We know this stuff is complicated, but it is your responsibility to understand and make sure your app conforms with all local laws […]. And of course, apps that solicit, promote, or encourage criminal or clearly reckless behavior will be rejected. While your app has been removed from the China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan App Stores, it is still available in the App Stores for the other territories you selected in iTunes Connect.”

iTunes Preview of 10 years: Source

Apple also censors Apple TV projects that “may offend China” and told Apple TV partners to “avoid portraying China in a poor light.” Apple’s current censorship of Apple TV, banning content that may offend Beijing, is thought to be directly linked to the 2016 iTunes ban

Apple Music & iTunes Songs

In 2019, Apple Music removed a song by Hong Kong singer Jacky Cheung from its streaming service in China because of the politically sensitive lyrics it contained. The song, entitled “The Path of Man” (人間道), which was the theme music of the 1990 film A Chinese Ghost Story II, is directly referring to the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre.

Apple Music’s users also discovered that the songs of Hong Kong singer Anthony Wong and pro-democracy singer Denise Ho were taken down from Apple Music’s China service. Denise Ho, who supported the 2014 Umbrella Movement, could not be searched on the platform.

Sophie Richardson, China Director at Human Rights Watch, posted commentary on the takedown to Twitter, calling the decision to remove Cheung’s song “spectacularly craven, even by [Apple and Tim Cook’s] standards.”

Spectacularly craven, even by @apple @tim_cook standards--which is saying something. Apple Music in #China removes Jacky Cheung song with reference to Tiananmen massacre https://t.co/1u6n36Oelm via @hongkongfp

— Sophie Richardson (@SophieHRW) April 9, 2019

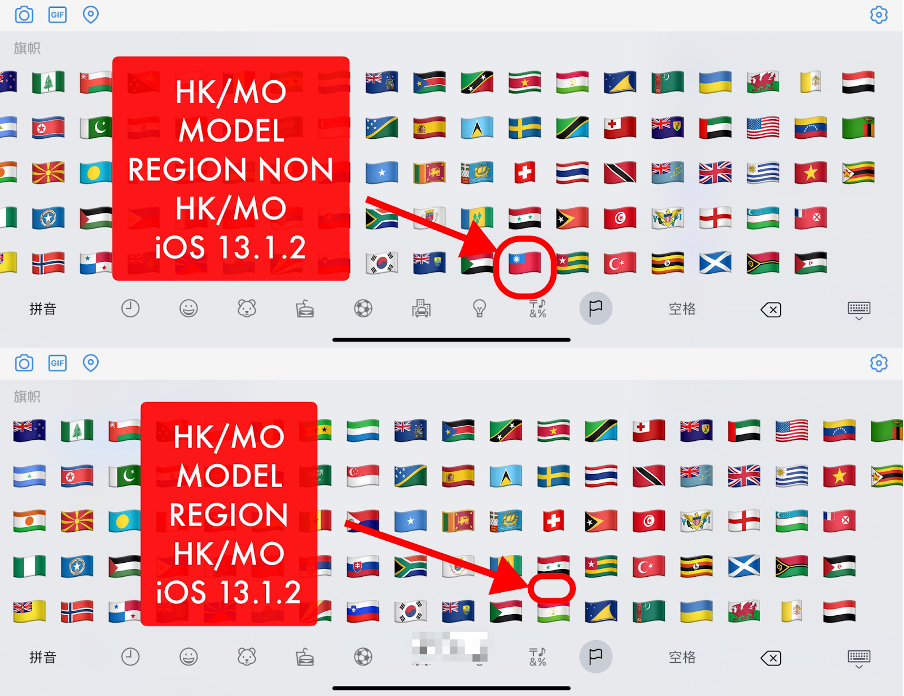

Emojis

In September 2019, Apple censored the Taiwan flag emoji for users that have their iOS region set to Hong Kong or Macau. However, the flag emoji did not completely disappear and was still shown in apps and on websites, or could be typed in English by users. Apple had only previously applied such censorship to users who had set their iOS region to mainland China. Since 2017, Chinese iOS users have been unable to see or type the emoji on their devices at all.

Retail Employee Attire

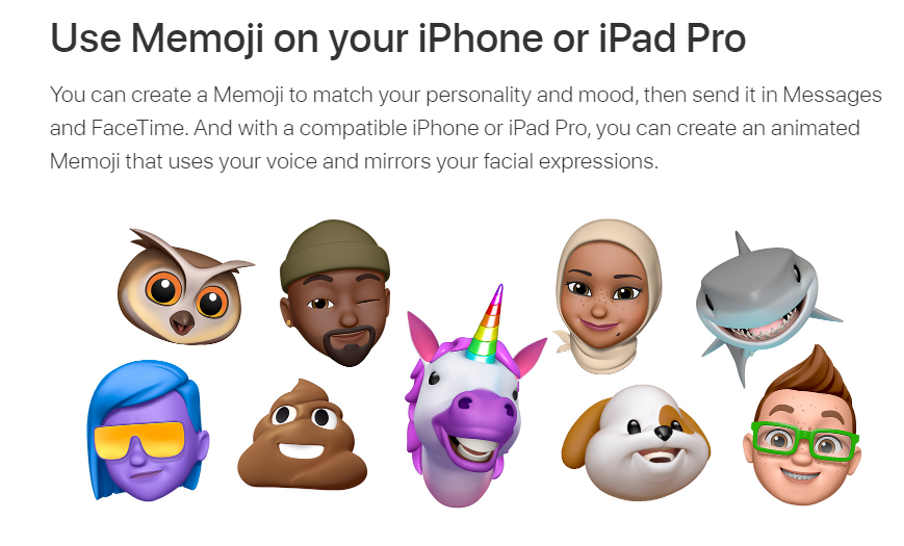

In August 2020, managers at Apple stores in Hong Kong banned employees from expressing their support for the city’s pro-democracy movement. Prior, staff at Apple stores globally have been wearing lanyards with Memojis—or customizable emoji characters—as part of a way to “help store employees express themselves in a world wearing masks.”

Apple encourages its customers to personalize their Memoji “to match (their) personality and mood”, but prevented its employees in Hong Kong to do the same. Source: https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT208986

According to activist Joshua Wong, Apple managers in Hong Kong have ordered staff not to decorate their Memojis with yellow or black accessories after some staff members personalized theirs in a way that was interpreted as pro-protest support.

In a forwarded WhatsApp message shared by Wong, one Apple employee said a manager questioned a worker’s choice of Memoji colors, asking “Do you really like black/yellow? Why wear a yellow shirt/yellow hat?” “After that, [the manager] forced [my] co-workers to immediately change their Memoji colors. Otherwise, they could not leave,” the message continued. It added that managers have even threatened not to renew the contracts of staff as a way to pressure them to change their Memojis. The employee also said that staff have instructed them not to wear face masks that are yellow or have the word “Hong Kong.”

Wong published an open letter that he had emailed to Apple CEO Tim Cook, asking him to protect free speech in the company and create a welcoming work environment.

“I hope Apple can affirm its commitment to the principle of freedom of expression and introduce concrete measures to protect employees from future workplace censorship,” Wong wrote in the letter, which remained unanswered.

Engraving

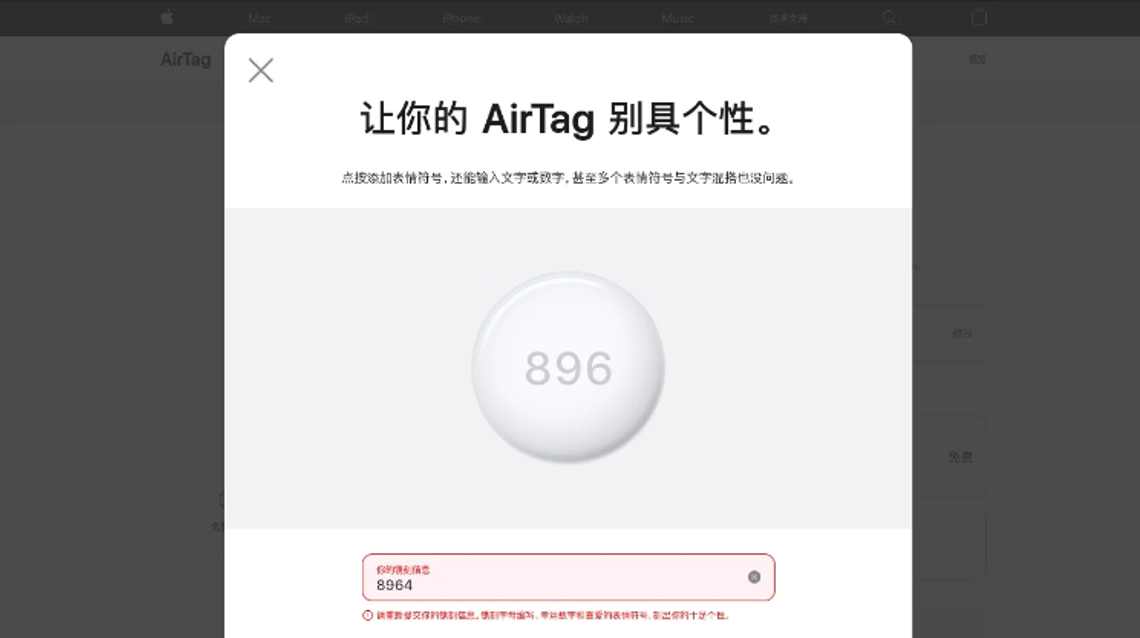

The engraving “8964”, a reference to the 1989 June 4th protests, is politically censored on an AirTag in mainland China.

Apple’s restrictions on what can be engraved on its devices as a way to personalize them have been known for some time now. In 2014 the Los Angeles Times was already publishing an article on the politically charged words that would be rejected by Apple’s online store engraving service in China. Words like “Dalai Lama’s name in Chinese characters, Tibet independence” or “Liu Xiaobo” would trigger a pop-up box saying: “The engraved text is not suitable”.

In 2018, Hong Kong Free Press reported that the names of some Chinese state leaders and activists had been deemed “not suitable” from the latest versions of the iPad, iPod Touch and Apple Pencil’s engraving service.

After the news of sensitive words being censored by Apple’s online store engraving service in China came out for the third time, in April 2021, The Citizen Lab decided to look further into this specific type of censorship across six regions, including mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

“Among the keyword filtering rules we discovered in the six regions we tested, the largest number applied to mainland China, where we found 1,045 keywords filtering product engravings, followed by Hong Kong, and then Taiwan.” the Citizen Lab’s report said.

Interestingly enough, Citizen Lab suggested that Apple’s staff in charge of blocking specific words) might not fully understand what content they filter in Chinese language regions:

“By comparing Apple’s Chinese language lists to those we have previously found used to censor other Chinese products, we found that Apple’s list has similarity to many that is unexplainable by coincidence. Rather than each censored keyword being born of careful consideration, many of Apple’s censored Chinese keywords seem to have been thoughtlessly reappropriated from other sources.”

If that was the case, it would be a contrary example of how Apple seems to curate its App Store, with high-ranking executives directly involved in the decision process leading to the removal of apps for political motivations.

Government Surveillance & Data Requests

After the Hong Kong government granted the police vastly expanded powers under the national security law, including ordering platforms and internet service providers to remove content and hand over user information, major tech companies like Google, Twitter, and Facebook announced that they would halt the processing of data requests from Hong Kong authorities. Notably absent was Apple, which only said that it was “assessing” the impact of the new legislation.

Apple claimed it does not get data requests directly from the Hong Kong government. “Apple has always required that all content requests from local law enforcement authorities be submitted through the Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty in place between the United States and Hong Kong,” the company said. Under that process, “the U.S. Department of Justice reviews Hong Kong authorities’ requests for legal conformance.”

On its website, Apple gives a fragmented view of the data requests received from governments. Charts and data are organized per half-year and year-on-year trends are absent.

When looking at the evolution of the figures, the main observations that can be made, are:

- From 2013 to 2016, the number of “Device requests”, “information regarding customers associated with devices and device connections to Apple services” sent by the authorities of Hong Kong and to which Apple complied has more than tripled.

- From 2016 to 2020, the number of Device requests has significantly dropped, with only 5% of the number of requests in 2016 (1333), observed in 2020 (62). Those numbers continue to drop in the first half of 2021.

- Apple’s compliance with government’s requests has significantly dropped in 2020, although the data makes it clear that Apple did not pause Hong Kong Customer Data Requests in the region.

Requests for Customer Data in Hong Kong from 2013 to 2020

Source: https://www.apple.com/legal/transparency/hk.html

The very low number of Device requests sent by the authorities in 2020, when the NSL was adopted, shows no correlation between the crackdown on the civil society and requests for iOS users’ data sent to Apple. However, without the details of those requests, it is impossible to rule out the possibility that the authorities may have relied on evidence obtained via Apple’s device related data requests, to target those exercising their free speech online, including owners of Facebook groups, Telegram channels and web forums administrators.

Apple did reject a majority of Customer Data requests in 2020, potentially indicating a rise of unsubstantiated or illicit demands from the authorities.

However, since 2017, when Apple started reporting it, the number of “Financial Identifiers requests” (such as credit/debit card or iTunes Gift Card) has more than doubled. Although Apple vaguely defines the information that is transmitted to the government agencies requesting them, such identifiers could allow the police to know which apps have been purchased by a given user, even if the app was deleted by that user. Apple gives no explanation to this rise of “Financial Identifiers requests”.

Apple’s Compliance Rate